Increasingly powerful storms and super typhoons caused by climate change pose a major threat to some of the planet's most fertile reef ecosystems. So what can we do about them?

As climate change intensifies throughout the Coral Triangle, coral reefs will need to survive stronger storms. How exactly do typhoons affect corals?

Storms and typhoons continuously shape the composition, distribution and range of the world's reefs. Like plants, many corals take on forms best suited to their homes. Corals in areas pounded by strong waves have learned to grow dense, tough and compact colonies, while those in calmer waters maximize space to grow long, elegant but delicate branches.

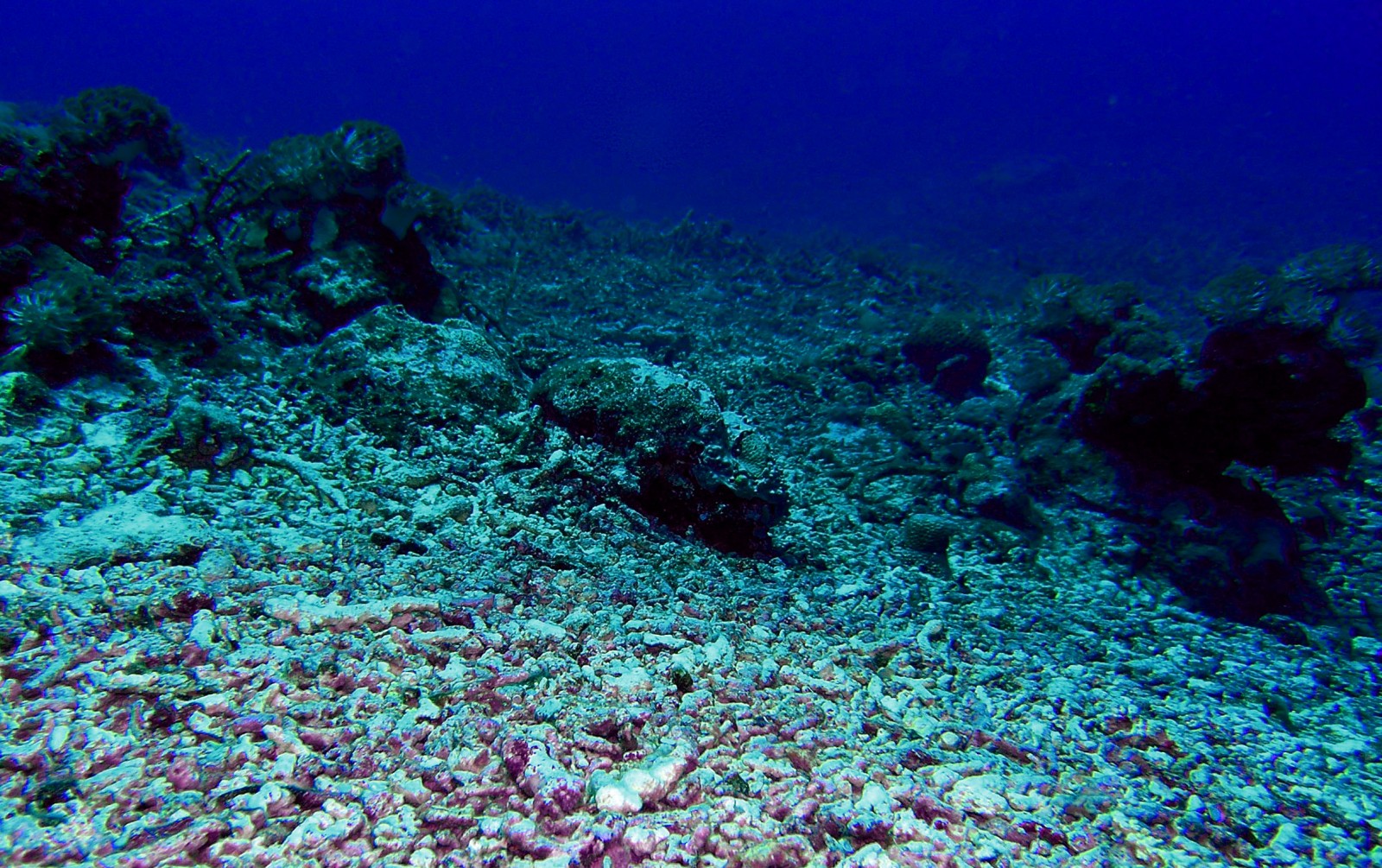

Solidly-built, rock-like species like brain coral can withstand much more punishment than branching or leaf-like corals. When a super typhoon hits though, nasty currents are the least of a reef’s problems. Powerful storm surges can pull debris like logs and rocks out to sea, where wave action rolls them around, smashing the seabed in a brutal game of coral crush.

Sand stirred up by violent waves can smother and choke off corals and other invertebrates like sponges and giant clams. Finally, too much rainwater can engorge rivers, causing them to discharge massive amounts of nutrient-rich mud, blanketing reefs and spurring blooms of fast-growing seaweed or algae which can outcompete corals for space and sunlight. The result? Decades, even centuries of growth can be destroyed by a single super typhoon. Why is this a problem?

Coral Reefs Give Us Food

Because over 120 million people in the Coral Triangle – which spans the waters of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Timor-Leste – directly rely on the sea for food and livelihood. With limited land space and stronger, crop-destroying storms, coastal communities will turn to fishing to feed themselves – and coral reefs form one of the richest hubs of oceanic productivity. Healthy reefs annually produce 30 to 40 metric tonnes of seafood per square kilometer.

But even the largest reefs can be destroyed by storms.

Apo Reef

Situated off the coast of Occidental Mindoro in the Philippines, Apo Reef is the largest in Asia and the second largest on Earth, after the Great Barrier Reef. It covers 34 square kilometers and hosts almost 200 coral species. Apo Reef Natural Park became a no-take zone in 2007, curbing illegal fishing activity. Fish biomass breached 76 tonnes per square kilometer. Even after full protection though, Apo Reef suffered extensive damage from the climate change-spurred super typhoon Caloy in 2006.

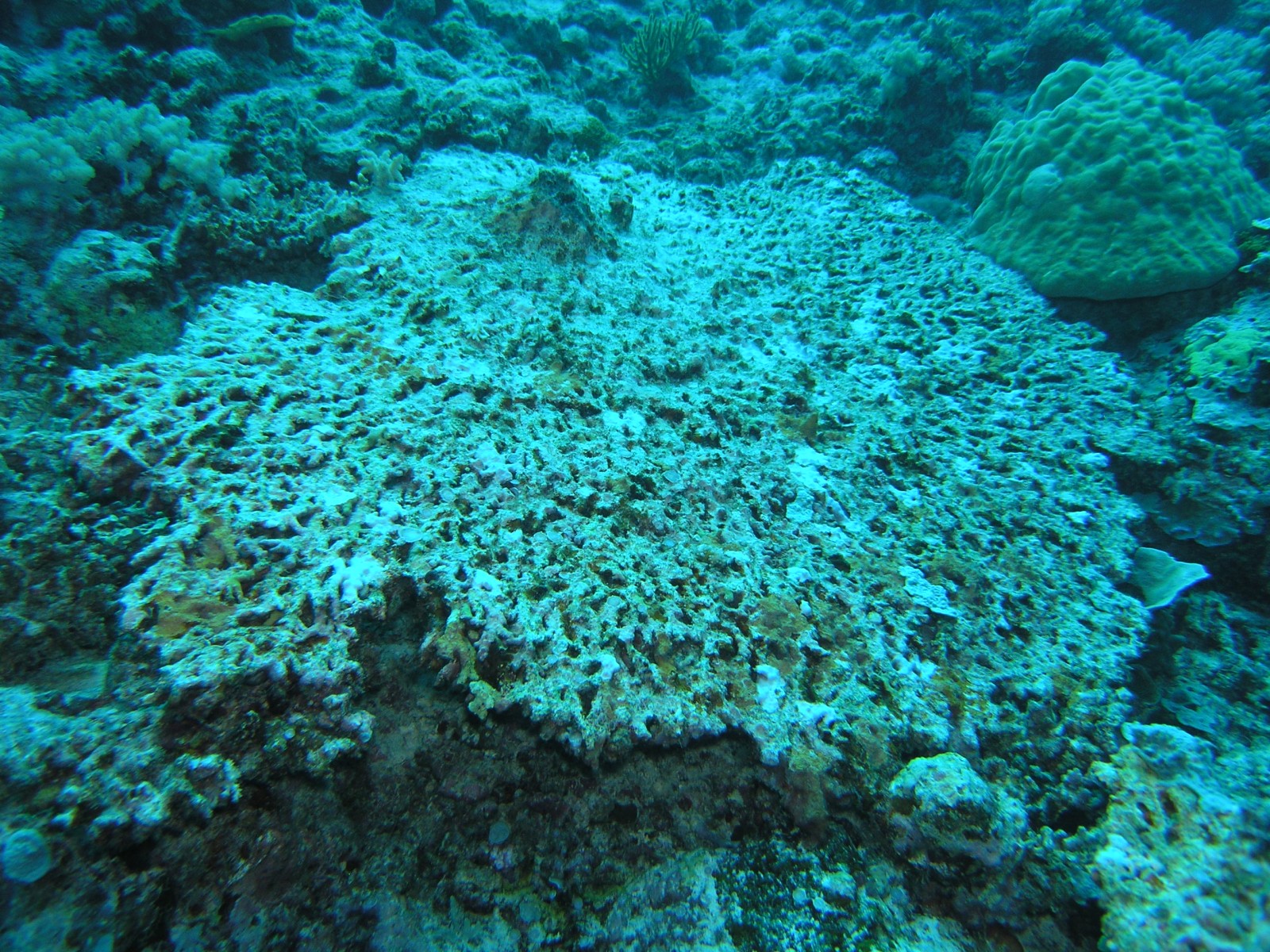

In 2006, WWF pegged Apo Reef's hard coral cover at 52%. After typhoon Caloy, it dropped to 16%. “It looked exactly like a deforested jungle,” recalls WWF-Philippines Mindoro Project Manager John Manul. “Giant table corals were uprooted. Broken coral branches were everywhere. Even the distinctive haze that envelopes burnt-out forests was replicated, because even after a week, the water was milky from stirred up sand.”

As super typhoons dramatically erode the capacity of coral reefs to provide people with seafood, we need to find better ways to protect them.

Steps to Save Reefs

About 85% of the reefs in the Coral Triangle are directly threatened by local human activities, substantially more than the global average of 60%. Asia’s growing population and climate change are placing extreme pressure on its seas. Through a business-as-usual scenario, as much as 60% of Earth’s reefs may die by 2050.

Good thing that creative ways to conserve coral reefs are sprouting up. Launched by a Filipino airline in 2008, Bright Skies for Every Juan enjoins people flying with Cebu Pacific Air to indirectly offset their flight’s carbon emissions by making online donations to climate change adaptation projects for both Apo and Tubbataha Reefs in the Philippines. “Though reefs have seen through millions of years of storms, the combined effects of climate change, pollution and overfishing might push some over the brink,” explains Manul.

“However, healthy coral reefs have a way of bouncing back – provided that they are shielded from human impacts. The full range of biodiversity contributes to overall reef resilience. By curtailing illegal fishing and poaching, we shall maximize their chances of recovery.” Due to enhanced protection and improved fisheries management, Apo Reef’s coral cover was able to recover to 32% by 2011 – a healthy sign that with a little more protection, Earth’s coral reefs can weather the storms of the future.