New satellite tracking data shows just how far Coral Triangle turtles travel to mate and nest...but those nesting sites are sinking beneath the waves.

Of the seven species of marine turtle found on Earth, six of them occur in the Coral Triangle. These same six are also listed as vulnerable or endangered by CITES – Hawksbills and Kemp’s Ridleys are critically endangered. Mapping turtle movements using satellite tags is a key first step in being able to effectively protect them from threats like habitat loss, illegal fishing and climate change.

That’s why Conservation International (CI) decided to place satellite tags on ten turtles within the Coral Triangle. A CI team travelled to Timor Leste and Papua New Guinea (PNG) where they were able to place tags not only on Green Turtles, which are relatively common, but also an Olive Ridley turtle and five critically endangered Hawksbills – a welcome surprise for the researchers, since they are far less common than their Green cousins. While Green Turtles tend to feed on seaweed, Hawksbills prefer to eat sponges on coral reefs, which is to say there are different challenges in protecting separate turtle species.

According to Niquole Esters of CI’s Coral Triangle Initiative, the tagging was a delicate operation that required patience. We patrolled the beaches about every four hours looking for tracks,” she explains. “When the turtle is nesting, it goes into a zone — it’s so focused on what it’s doing that it doesn’t notice the things around it. If we were lucky, we could find the nest and tag the turtle while it was nesting because it wouldn’t notice us.”

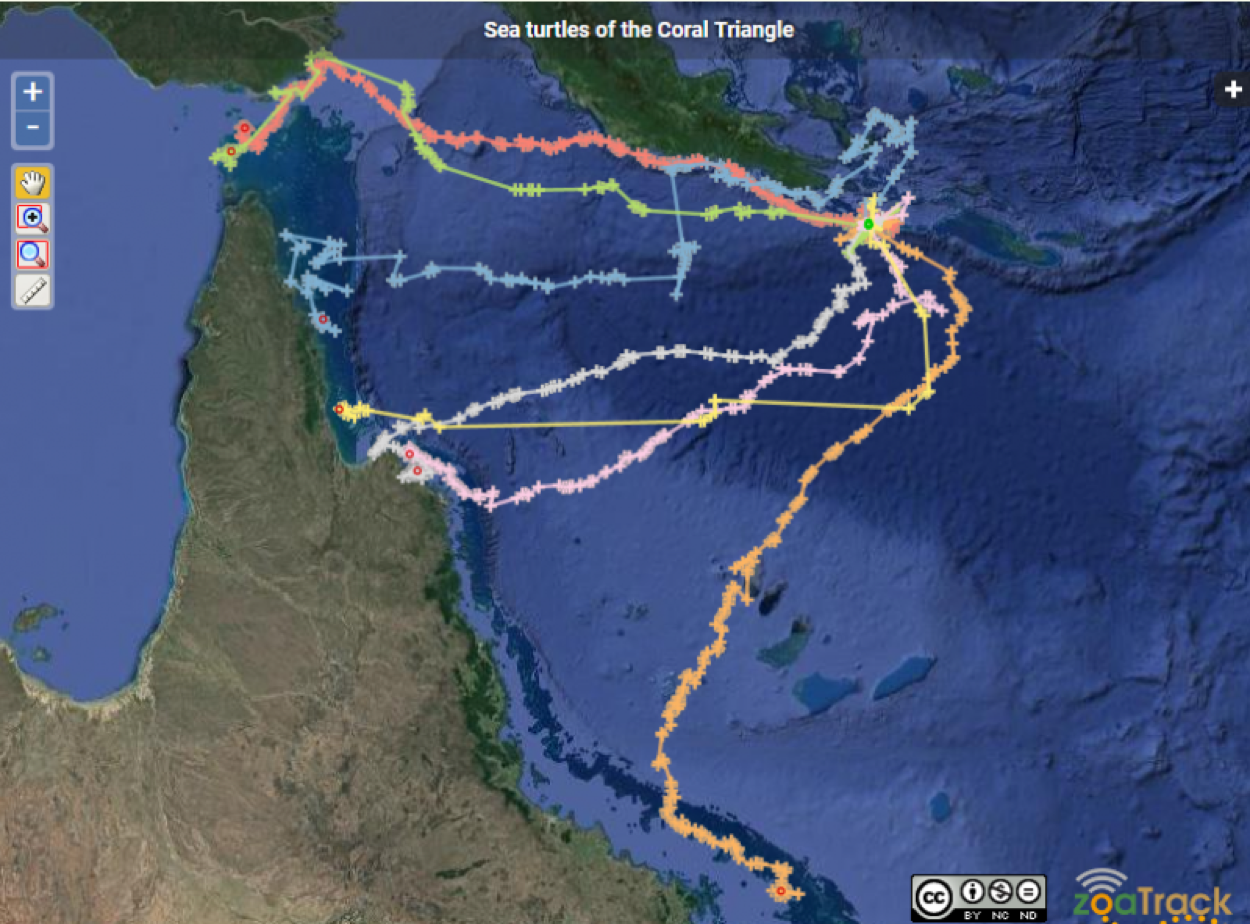

The satellite tags – attached securely to the turtle’s carapace – transmit data in real time which is logged on a free to use animal tracking website. The tags transmitted data from December 2017 through March 2018, revealing some unexpected migratory patterns.

“We found that the turtles are migrating to Australia [which] starts to open up avenues for conservation and for partnership across countries,” says Esters. “The whole sea turtle pathway includes the Great Barrier Reef and the Coral Sea [meaning] these guys swim hundreds and thousands of miles.”

Turtles of course have little time for national borders – but they are impacted by them. The fact that they travel between the Coral Triangle and Australia is good to reason to develop multilateral partnerships to safeguard the ecosystems they pass through on their long journeys.

The elephant in the room however is climate change. According to Esters, the inhabitants of the small islands the team visited to tag the 10 turtles all reported that their islands were shrinking. Besides the looming threat of displacement faced by these islanders, turtle nesting sites will disappear.

“The islands are shrinking so much but the turtles are still coming, so they’re digging up each other’s nests because their imperative to nest is so overwhelming…When a turtle doesn’t make it to the beach in time, they end up laying their eggs in the water on the way to the beach.”

Understanding the extent of the problem gives some hope that action can be taken to mitigate the impacts of climate change and other human threats. Over the next few years, CI plans to tag more turtles so that there’s sufficient data to really understand how these turtles tend to travel over longer time cycles.

Turtles are one of the more iconic sea creatures – much loved not just to divers, but by most people – so the public tends to get behind efforts to protect them. And of course, protecting turtles means sustaining the ecosystems that they rely on for their survival.