Sabah, Borneo is home to some of the best diving in the world. But confusing regulations by the Malaysia authorities are seeing shark populations here being decimated. It's time for action.

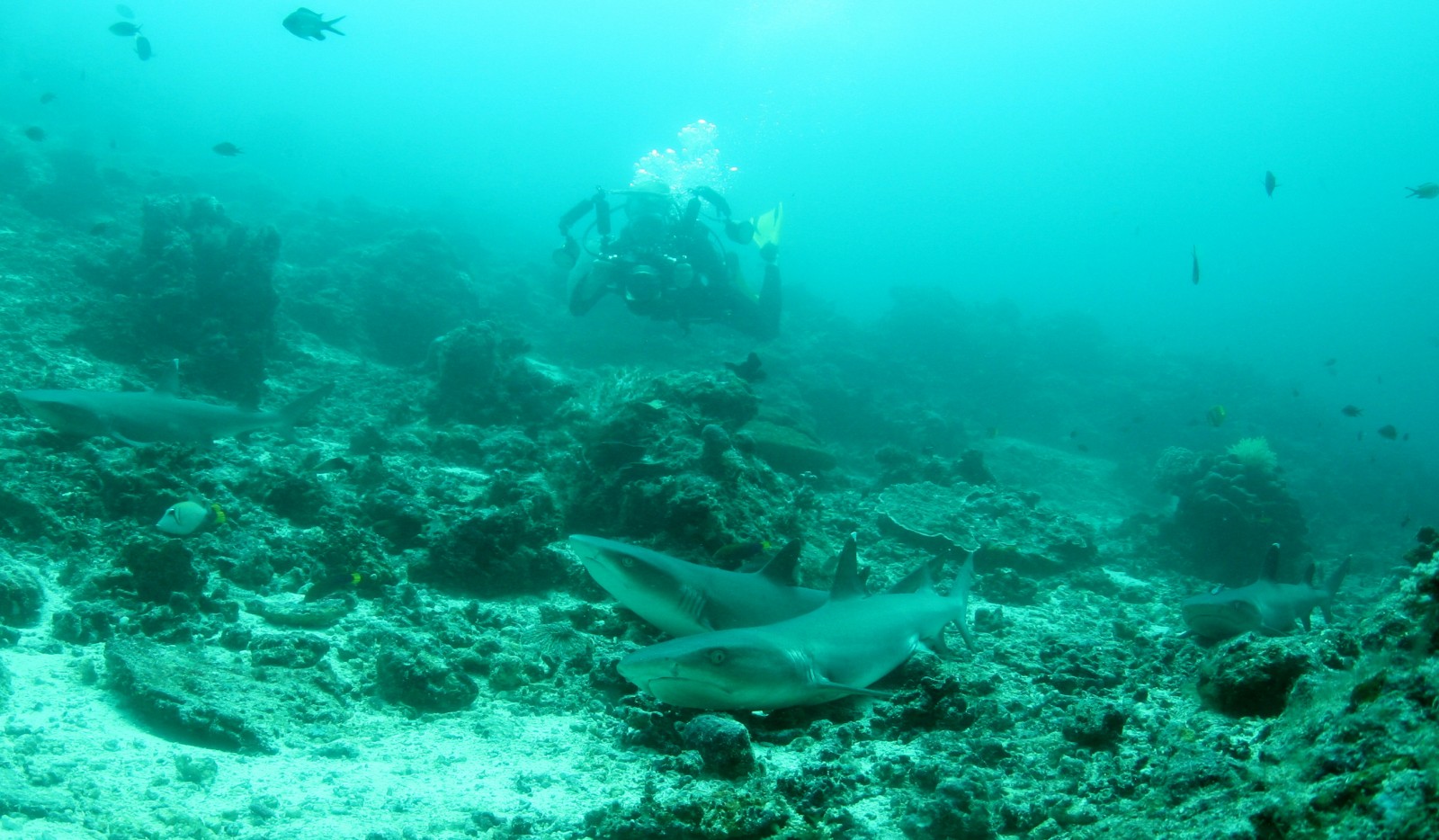

The shark appears from the blue, soaring in the current like a 707 in a holding pattern. Doglike, the curious shark investigates open mouthed, eyeing my friend’s flippers. Six feet long and sinuous, she glides along behind us until wth a switch of her tail and a flare of her pectoral fins, she is off, gliding down the coral bank at the south end of Sipadan Isalnd. I turn to my buddy Aaron “Bertie” Gekonski - he blows bubbles and gives a thumbs up.

Encounters like this are more rare than they used to be, but they still thrill veteran shark divers like us. Bertie made himself famous in the dive community by circulating a shark selfy with a school of sharks a few years ago, and is now the host of online conservation series Borneo From Below and a new show called Borneo Warriors. We have been filming one of these episodes on the Sharks Of Sipadan on the southeast edge of Malaysian Borneo. Protected by the Malaysian government and a major international dive destination, Sipdan is one of the few dependable locations to find sharks in the region. Sadly, these diving experiences are disappearing as sharks are being fished out of the seas.

To the north of Sipadan is the resort island of Mabul. Besides diving an artificially constructed house reef, the main attraction is that Mabul is the gateway for divers to Sipadan and hosts over fifteen dive resorts and homestays. The island is also home to nearly 3000 native people who live on or above the water and subsist from the sea, or working at the dive resorts. Once home to her own population of sharks, overfishing has all but erased sharks on this and nearby islands. Not long ago, tourists returning from their shark dives would see local fishermen slaughtering sharks at Mabul. Concern about sharks and their business lead dive operators and conservationists to form an alliance and convince the Sabah minister of Culture Environment and Tourism to pass a law protecting sharks. In 2013 the law banning shark fishing in the entire state of Sabah went into effect.

At 360 million US annually, tourism is big money in Sabah. The Sabah Minister of Tourism, Culture and the Environment Datum Seri Masidi Manjun appreciates that and has been a champion for protecting natural resources and sharks. Following the no shark fishing law, eco-operator Scuba Junkie and other divers convinced the local fishermen that fishing sharks was illegal and they had to stop. For a time, tourists were no longer treated to bloody water and piles of shark fin and dismembered carcasses of the sharks they came to dive with. That victory however, was short lived.

The Malaysian Federal government rejected the state law, claiming sharks fished offshore could be landed in Sabah waters. Learning this, the fishermen on Mabul are again treating visitors to images of bloody water that recall the Taiji dolphin slaughter. As far as can be determined, the fishermen are not fishing illegally, although no one has confirmed where the reefs sharks are caught. Unfortunately, the reef sharks at Mabul and nearby dive destinations are all gone, and these fishermen are traveling farther afield to harvest sharks.

Returning from our dive on Sipadan last year, we encountered a longboat tied up at the water-village adjacent to one of the resorts. The fishermen were filleting reef sharks but when we pulled our boat up they dragged the bodies behind the boat to conceal them. When asked why they were killing sharks, the men became angry and ordered us to leave. The next morning I swam to the house and photographed the carcasses of two grey reef sharks in the water beneath the dock. In July new images of slaughtered sharks went viral, with internet petitions and letters decrying the slaughter. International and internal protest have brought unfavorable attention to this small tropical island, and raises a bigger question: how do we protect sharks and accommodate a growing population dependent on the sea for their livelihoods?

Driven largely by profits from the shark fin trade, these fishermen are supporting themselves in a more profitable fashion than their non-shark fishing neighbors. Their boats are larger and have a longer range allowing them access to islands on the Indonesian border. But one questions how long this can continue, and what will happen to the dive tourism industry when the sharks are all gone. Perhaps even more important is the ecological role reef sharks play. Sharks are critical for the health and balance of ocean ecosystems. Overfishing sharks has a cascade effect that impacts the rest of the food web. Simply put, a healthy ocean ecosystem needs sharks.

Protecting habitat is one solution that can benefit sharks. In July, Sabah Minister Mr, Masidi signed into law the largest marine protected area (MPA) in the country. The Tun Mustapha Park (TMP) occupies 1m hectares (2.47m acres) off the northern tip of Borneo. This adds to two other large marine parks in Sabah including the Tun Sakaran Marine Park in Semporna, making six marine parks on Malaysian Borneo. However, these parks still allow fishing and will do little to protect large sharks. To counter this, Mr. Masidi has announced he will make these MPAs shark sanctuaries, yet the conflict between agencies and laws cloud the issue. Under current law, unless the shark is a federally protected species like whale sharks, sharks are managed under the fisheries department, whose has not recognized the need to increase protection for sharks and rays.

Legal or not, the unwanted attention on shark fishing driven by tourists is supporting the building movement for marine protection in Sabah. International groups like WWF and grass roots conservation groups like Sabah Shark Protection Association (SSPA) are taking advantage of the attention and encouraging leadership to increase protection for sharks and marine habitat while supporting community based conservation.

Recently Natural Resources and Environment Minister Sewri Dr Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar proposed a law placing sharks under his ministry. This law would help the few species listed as endangered or CITES protected species like hammerhead sharks and manta rays. It is unclear if increased protection would be afforded to all shark species including reef sharks but protecting threatened species is an important start.

While increasing no shark fishing, strengthening fin trade and creating shark sanctuaries, alternative livelihoods must also be considered for these and other fishermen who are fishing the reefs of Semporna. Developing ecotourism and eco-conservation opportunities is a major part of the solution in Sabah. A socioeconomic surely conducted by the Australian Institute of Marine Science placed the value of one reef shark at $815,000 US dollars to the local economy in its lifetime. At a one-time profit of approximately $100 for a set of fins, sharks are more valuable alive than dead.

Flashing back on my recent experience diving with a live shark, and compared to the images of the slaughtered sharks I am convinced sharks have additional value. Aside from their importance to the health and balance of the marine ecosystem, and financial benefits to the local economy, sharks have an inherent aesthetic and spiritual value. Diving with sharks in their natural ecosystem is a mystical experience that resonates with our role as humans in the wild. With the SSPA and the eyes of international dive tourists, Shark Stewards is working through the SSPA and the government, led by Ministers. Masidi and Junaidi, to increase shark and reef protection and to protect sharks and rays for the future of Borneo wildness.

Learn more about the sharks of Sipadan and how you can support saving Sabah sharks at www.sharkstewards.org